A little while ago, we ran a very well received webinar with Simon Wardley presenting the essentials of his innovative mapping approach.

We have been working to integrate this into our enterprise and business architecture meta models and approach. Early results are encouraging. We have found the following:

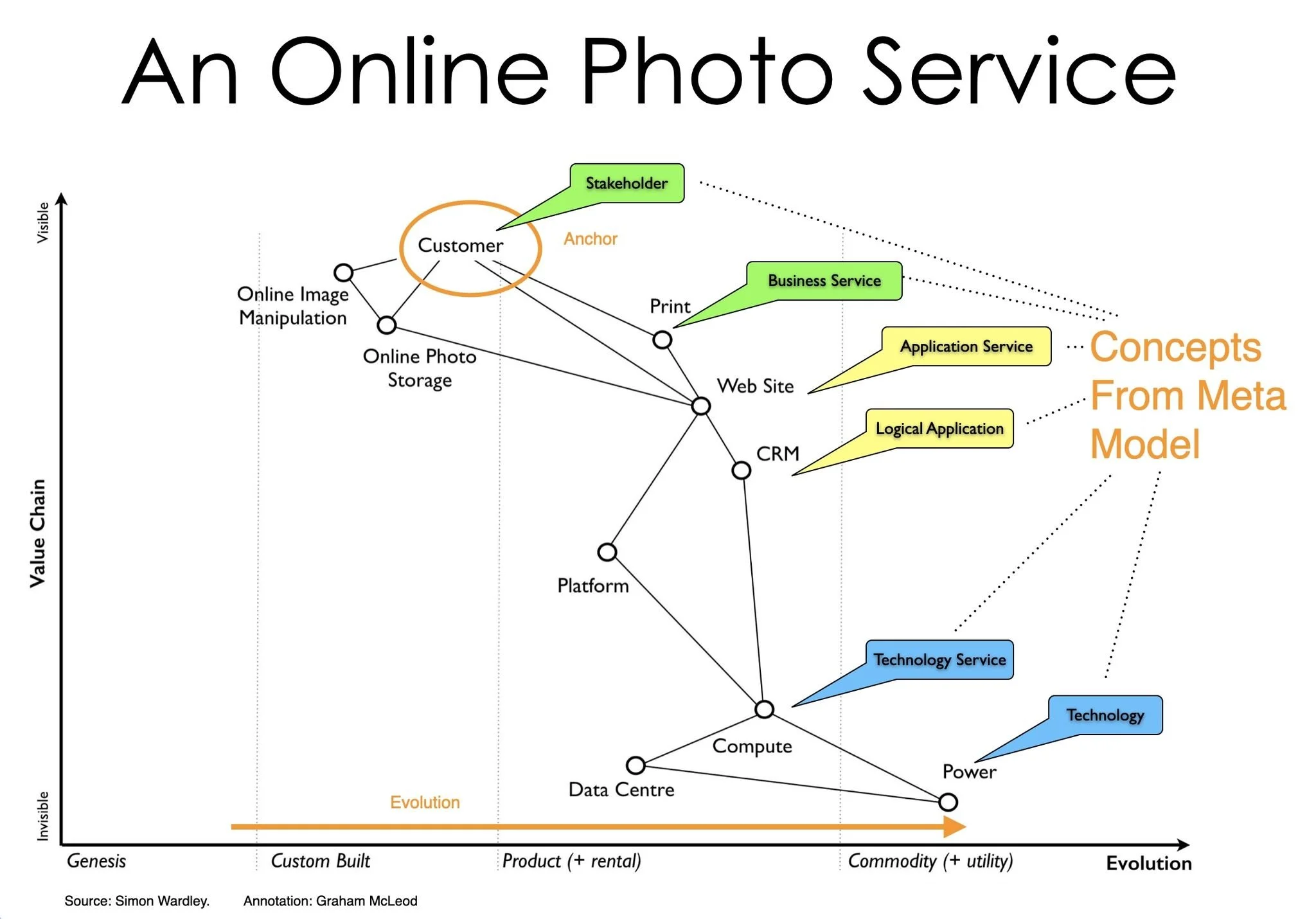

Maps can be thought of as similar to graphical models, but with axes that facilitate placing elements in spatial dimensions (specifically how close to the delivery of value / visibility to client they are (Y axis) VS how evolved they are in terms of how they are delivered (X axis). This means we can easily adapt existing graphical models and tools to also have axes and support maps

The elements in the maps range from Customers (one subtype of Stakeholder), through Products and Services (Offerings), the elements necessary to deliver these (e.g. Processes, Systems) and those supporting them (e.g. Technology, Data). The good news is that these are already included in our Holistic Architecture Language meta model and have associated visual representation. We can use our existing ones or just dots as preferred

The idea of evolution fits well with our existing concepts of Maturity Level for various elements and capabilities

Bottom line: Mapping fits very well and provides additional value by allowing identification of trends and potential scenarios. It also allows visual grouping that helps planning in terms of suitable methods, responsibilities and timing.

We are holding an initial one day workshop on leveraging mapping within architectures for those who would like to dig deeper…

See this page for more information on the Wardley Mapping for EA Workshop

Image Credit: Simon Wardley

Annotation: Graham McLeod